Fix point combinator in Rust

Table of content

It has been many years since Haskell discovered the Y combinator(fix point combinator). It's such a milestone that it makes lambda calculus turing complete. Let's try to implement it in Rust and have fun!

Fix point of a function

What do we mean by "fix point"? Well, in fact, it's quite simple. A fix point of a function $f$ is a parameter $x$ with the following equation:

$$ f(x) = x $$

This does not seem to be fun... But if we try to flip the equation, it's quite interesting:

$$ x = f(x) = f(f(x)) = f(f(f(x))) = f^n(x) $$

If we can find a fix point, then we have recursion and loops for free! Now suppose we want to build a magic wand Y, for any function $f$, whenever we apply the wand to $f$, we automaically get the fix point of $f$, that is:

$$ Y(f) = f(Y(f)) $$

$Y(f)$ becomes the fix point of function $f$! But does this magic wand exist? Haskell said YES!

figure 1

Self as parameter

Before we actually find the magic wand, let's first try to consider another question:

QUESTION:

Can we write recursions using pure lambda expressions without name binding?

For example, if one want to write a recursive factorial function:

fn fact(n: usize) -> usize {

if n == 0 {

1

} else {

n * fact(n - 1)

}

}

If we cannot use name binding, then we cannot use name fact inside function definition of fact:

fn fact(n: usize) -> usize {

if n == 0 {

1

} else {

n * todo!("how???")

}

}

Well, since we cannot directly bind the name, let's try to pass a function as it self:

fn fact(f: &dyn Fn(usize) -> usize, n: usize) -> usize {

if n == 0 {

1

} else {

n * f(n - 1)

}

}

But the problem still remains. How do we pass the parameter f?

Repeating self?

In method above we have no way of passing the function of itself f. But we may imitate the function call itself:

fn fact(this: &dyn Fn(todo!("?"), usize) -> usize, n: usize) -> usize {

if n == 0 {

1

} else {

n * this(this, n - 1)

}

}

No way out. If we are in dynamic typed languages then we are done. But in static typed language like rust, we cannot express the type of this. To see why, consider expand the type of this:

this: &dyn Fn(&dyn Fn(todo!("?"), usize) -> usize, usize) -> usize

this: &dyn Fn(&dyn Fn(&dyn Fn(todo!("?"), usize) -> usize, usize) -> usize, usize) -> usize

//...

We are repeating the type again and again which leads to inifnite type!

Ω combinator

Typing is hard. Let's for now forget about types and focus on finding the general way to do recursion in dynamic typed languages. We are now convinced that recursion can definitely be implemented without name binding in dynamic typed languages(see previous section).

Recall the pattern of repeating self, we can pass the function itself into itself:

λf. f(f)

which looks weird. But remember in this way we can pass the function itself into f? Let try to pass it:

(λf. f(f))(λf. f(f))

and try to reduce it(replace f in the first lambda with the passed parameter):

(λf. f(f))(λf. f(f))

WOW we just get the original expression back! This kind of combinator is so interesting that we call it the Ω combinator:

$$ \omega(x) = x(x) $$

omega => OMG it's a recursion without name binding!

Recursive type

Typing is hard.

We are now getting really close to the real magic wand! But we still need to fix the infinite type problem.

Remember, whenever you find something not exist, just create it! Let's create the infinite type in rust's type system. The first step of any creation if to try to express it in some way. Since we cannot directly express the inifinity, we pass the repeating part as parameter:

λa.e

Then we define a new operation unfold:

unfold (λa.e) = e[(λa.e)/a]

e[a/b] means to replace all occurences of b to a. Therefore we replace all as into λa.e it self. We can infinitely unfold the type as many times as we want.

In theory study, people call this kind of infinite type μ type and replace λ with μ:

μa.e

Simulate μ type in rust

Let's implement μ type in Rust! Recall the unimplemented type is like:

&dyn Fn(todo!("?"), A) -> B

Then we can create the U type:

struct U<'u, A, B>(&'u dyn Fn(U<'u, A, B>, A) -> B);

Now we have typed Ω combinator:

fn w<A, B>(u: &U<'_, A, B>, a: A) -> B {

u.0(U(u.0), a) // f(f, a)

}

Y combinator

We've got all prerequisites of our magic wand! Recall the Y combinator we want has the property:

Y(f) = f(Y(f))

To achieve this, we only need to add one f to the Ω combinator:

λx. f(x(x))

and pass this part to itself:

(λx. f(x(x)))(λx. f(x(x)))

= f((λx. f(x(x)))(λx. f(x(x))))

= f(f((λx. f(x(x)))(λx. f(x(x)))))

= f(f(f((λx. f(x(x)))(λx. f(x(x))))))

= ...

Believe it or not, we've created the Y combinator! Just abstract f:

λf. (λx. f(x(x)))(λx. f(x(x)))

Strict or lazy

If you implement the Y combinator above(try it!), you will find that the calculation will stack overflow! This is because this kind of version only can be applied to lazy evaluated language like Haskell. If we want to implement it in Rust, we have to choose a strictly evaluated version. Here's one:

λf. (λx. f(λa. x(x, a)))(λx. f(λa. x(x, a)))

Using this we can finally implement the Y combinator in Rust!

struct U<'u, A, B>(&'u dyn Fn(U<'u, A, B>, A) -> B);

fn w<A, B>(u: &U<'_, A, B>, a: A) -> B {

u.0(U(u.0), a)

}

fn y<A, B>(f: &impl Fn(&dyn Fn(A) -> B, A) -> B, a: A) -> B {

w(&U(&|u, a| f(&|a| w(&u, a), a)), a) //(λx. f(λa. x(x, a)))(λx. f(λa. x(x, a)))

}

fn usage() {

let fact = |f: &dyn Fn(usize) -> usize, i| {

if i == 0 {

1

} else {

i * f(i - 1)

}

};

let n = y(&fact, 5);

assert_eq!(n, 120);

}

Application in real world

At first glance, you may assume recursion without name binding is useless.

QUESTION:

What's the point of abstracting recursion this way if we can use name binding directly?

I used to assume that the Y combinator can only be useful in theory analysis. But I'm wrong. The power of fix point arises when we try to abstract general effects!

Memorizing fibbonacci

The fibbonacci series has a direct recursion implementation (in rust, for example):

fn fib(i: usize) -> usize {

if i <= 1 {

1

} else {

fib(i - 1) + fib(i - 2)

}

}

However, since fib is not efficient and has already been a fixed point, we cannot transform it into memorization version(i.e., the state side-effect):

fn mfib() -> impl FnMut(usize) -> usize {

let mut cache = HashMap::new();

move |i| match cache.get(&i) {

Some(n) => *n,

None => {

let n = fib(i);

cache.insert(i, n);

n

}

}

}

mfib is still $O(2^n)$! If a function has already been fixed as a fix point, we cannot change its complexity! Therefore there's no way we can reuse fib.

Applying the fix point combinator, we can abstract the function itself:

trait Fib {

fn run(&mut self, i: usize) -> usize;

}

fn fib<F: Fib>(f: &mut F, i: usize) -> usize {

if i <= 1 {

1

} else {

f.run(i - 1) + f.run(i - 2)

}

}

struct MemFib {

cache: HashMap<usize, usize>,

}

impl MemFib {

fn new() -> Self {

Self {

cache: HashMap::new(),

}

}

}

impl Fib for MemFib {

fn run(&mut self, i: usize) -> usize {

match self.cache.get(&i) {

Some(n) => *n,

None => {

let n = fib(self, i);

self.cache.insert(i, n);

n

}

}

}

}

fn test_mfib() {

let mut mfib = MemFib::new();

let n = fib(&mut mfib, 50);

dbg!(n);

}

Now we can safely reuse the fib function and reduce its time complexity to $O(n)$.

Notably, if you still want the original naive pure recursive version of fib, you can still build it as:

struct NaiveFib;

impl Fib for NaiveFib {

fn run(&mut self, i: usize) -> usize {

fib(self, i)

}

}

Finally, the fib function is composable both in pure fix point, but also in other effects!

F-Algebras and Lambek's lemma

Have you ever been curious that why recursion has been so useful and unbiquitous? Or, have you ever been curious that why products and coproducts are so important in both programming and math? Interestingly, there is strong explanation in category theory!

F-Algebra

Have you ever doubt the definiton of "algebra"? Mathematicians use the word "algebra" everywhere. In category theory, we abstract various kinds of algebras as F-Algebra: $$ F(a) \rightarrow a $$

For example, to represent Monoid m, we need two operations:

0: m

plus: m -> m -> m

a + b = plus a b

Then we can define $F(a)$ as: $$ F(m) = m^1 \times m^{m \times m} $$

Fix point as the initial object

Now that we have definition of algebras, does this definiton look familiar to you?

Recall the definition of fix point: $$ f(a) = a $$

The definition of F-Algebra only replace the = symbol to arrow! We can define an operator fix just as μ type:

type Fix f = Fix (f (Fix f))

Then define operators:

fix: f (Fix f) -> Fix f

unfix: Fix f -> f (Fix f)

You may now ask: What's the point of abstracting fix point this way? The secret lies in the relations of different kinds of F-algebras!

Suppose you have two F-algebras:

$$ F(a) \rightarrow a $$ $$ F(b) \rightarrow b $$

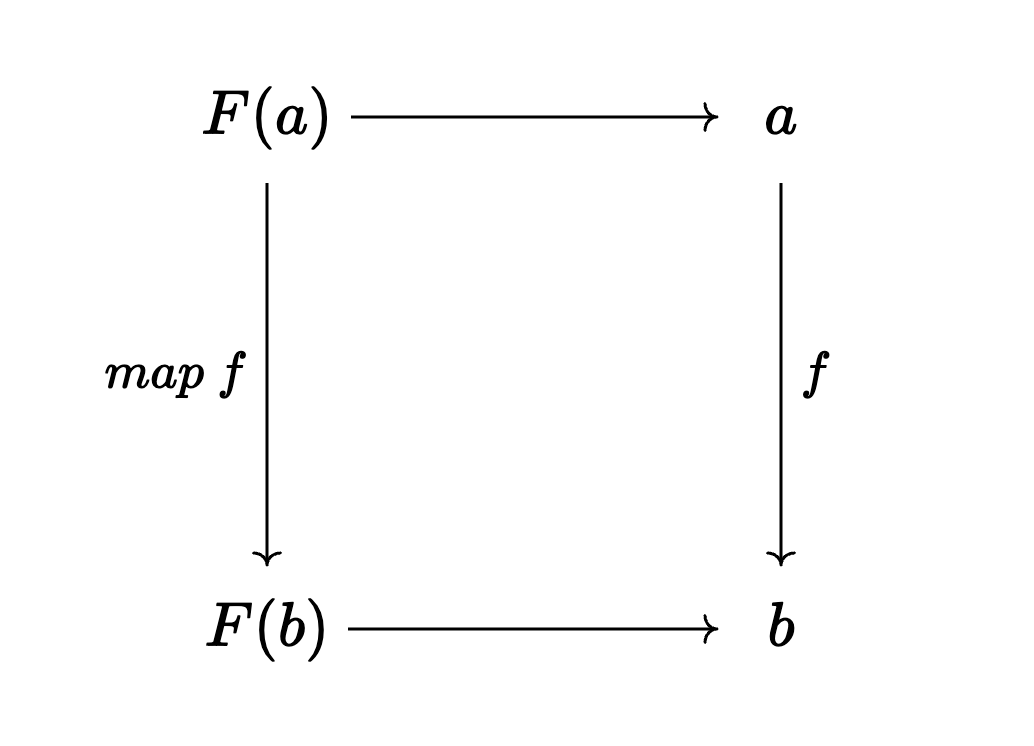

Viewing $F(a) \rightarrow a$ as one object, then we can define relations between $F(a) \rightarrow a$ and $F(b) \rightarrow b$ as: $$ f: a \rightarrow b $$ $$ (map\ f): F(a) \rightarrow F(b) $$

To better demonstrate the relation, we can use commutative diagram:

figure 2

If this diagram commutes, we say that we have relation $f$ from $F(a) \rightarrow a$ to $F(b) \rightarrow b$. Various kinds of F-algebras and relations between them forms a category! Now we ask an interesting question:

QUESTION:

Does this category have initial object? By initial object, we mean that, is there an object from which only exists one arrow to any other objects?

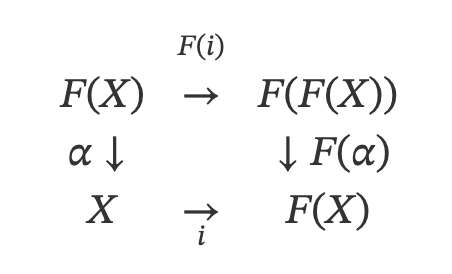

If we have this kind of initial object $F(x) \rightarrow x$, then we can prove that $x$ is a fix point of $F$ and: $$ F(x) = x $$ Instead of arrow, this time we have the final equality! Now we can conclude that recursion is important because it's the initial object in the category of algebras! and initial object implies some universal optimal construct!

If you are interested at the proof, try to follow the commutative diagram below!

lambek lemma proof